It was commonly believed that ancient hunter-gatherers, both humans and Neanderthals, had a simple lifestyle in which most or all of their food was obtained by gathering from local sources or by hunting animals from their environment. We simply assumed that beside the meat they hunted, their diet consisted of only raw foods such as wild plants, edible insects, mushrooms, honey, or pretty much anything that was safe to eat. Well, according to the recent study performed by Ceren Kabukcu* and her team from the archaeobotanical department of the University of Liverpool, we couldn't be more wrong.

Researchers analyzed charred food remains at two locations: the Shanidar Cave in Iraq and the Franchthi Cave in Greece. The food remains from the first cave originated from both Neanderthal hearths, 70,000 years old, and those from ancient humans thirty millennia later, and also those from Greece consumed some 12,000 years ago by our modern ancestors under microscopic examination reveal their very similar diet with the secrets of Paleolithic cooking of bitter-tasting vegetables.

Analysis of the food remains consists of different pulses, like fava beans and lentils, with traces of nuts such as wild almonds and pistachios, as well as yellow mustard seeds. They are common herbal species that can be easily found at the Shanidar site in the savannah-type vegetation. All these ingredients required careful preparation before consumption, including sophisticated cooking techniques such as soaking and pounding. Needless to say, researchers tried to prepare a similar meal and tasted the flavor. Chris Hunt, an expert in cultural paleoecology, said that 'it made a sort of pancake-cum-flatbread, which was really very palatable—a sort of nutty taste.'

The Guardian's Linda Geddes** has provided a full recipe with detailed cooking instructions, including tips on how to prepare patties the way Neanderthals did. Of course, I immediately got hooked, put on my hunting boots, and went to... well, the local food store to check if I could gather all the ingredients there.

However, even though I knew it would not be hard to find exact ingredients from Linda's recipe in the store, I was faced with a dilemma: should I follow the recipe to the letter or try my own variation? First of all, I thought of eggs. There's no doubt that Neanderthals easily collected eggs from various nests all around, and although they perhaps didn't use them in this particular meal, I thought it could be perfect to add some to the mixture. After all, eggs are a natural choice when it comes to binding different ingredients, and they contribute to the taste significantly. Also, the store provided a vast variety of different seeds and pulses, so I chose my own selection, and instead of pistachios, I found nice cashew nuts and goji berries. I'm sure there must have been at least one Neanderthal 70 millennia ago who would have agreed with my choice.

In the end, I created a mixture of all the ingredients from the above photo. In the mix with one cup each were mung beans (mungo pasulj), green and red lentils (zeleno i crveno sočivo), and finally millet and buckwheat seeds (proso i heljda). The mixture soaked for a night, and in the morning I cooked it only to the boil. After rinsing, I added grated almonds (bademi), cashews (indijski orasi), and goji berries (godži bobice), followed by three eggs, then shaped them into patties, and on medium heat, I fried them for a minute or two on each side.

I had low expectations for the reason I was not privy to the vegetarian cuisine that much, but I admitted I was wrong—the result was amazingly tasty Neanderthal burgers! The nutrition value was off the chart, and combined with mustard and ketchup, it was one great meal of the day. From what I learned in this cooking lesson, the real benefit lies in the zillion combinations with different seeds, pulses, and nuts. I am more than sure that with this, we now have one more regular recipe in the house.

Researchers analyzed charred food remains at two locations: the Shanidar Cave in Iraq and the Franchthi Cave in Greece. The food remains from the first cave originated from both Neanderthal hearths, 70,000 years old, and those from ancient humans thirty millennia later, and also those from Greece consumed some 12,000 years ago by our modern ancestors under microscopic examination reveal their very similar diet with the secrets of Paleolithic cooking of bitter-tasting vegetables.

Analysis of the food remains consists of different pulses, like fava beans and lentils, with traces of nuts such as wild almonds and pistachios, as well as yellow mustard seeds. They are common herbal species that can be easily found at the Shanidar site in the savannah-type vegetation. All these ingredients required careful preparation before consumption, including sophisticated cooking techniques such as soaking and pounding. Needless to say, researchers tried to prepare a similar meal and tasted the flavor. Chris Hunt, an expert in cultural paleoecology, said that 'it made a sort of pancake-cum-flatbread, which was really very palatable—a sort of nutty taste.'

The Guardian's Linda Geddes** has provided a full recipe with detailed cooking instructions, including tips on how to prepare patties the way Neanderthals did. Of course, I immediately got hooked, put on my hunting boots, and went to... well, the local food store to check if I could gather all the ingredients there.

However, even though I knew it would not be hard to find exact ingredients from Linda's recipe in the store, I was faced with a dilemma: should I follow the recipe to the letter or try my own variation? First of all, I thought of eggs. There's no doubt that Neanderthals easily collected eggs from various nests all around, and although they perhaps didn't use them in this particular meal, I thought it could be perfect to add some to the mixture. After all, eggs are a natural choice when it comes to binding different ingredients, and they contribute to the taste significantly. Also, the store provided a vast variety of different seeds and pulses, so I chose my own selection, and instead of pistachios, I found nice cashew nuts and goji berries. I'm sure there must have been at least one Neanderthal 70 millennia ago who would have agreed with my choice.

In the end, I created a mixture of all the ingredients from the above photo. In the mix with one cup each were mung beans (mungo pasulj), green and red lentils (zeleno i crveno sočivo), and finally millet and buckwheat seeds (proso i heljda). The mixture soaked for a night, and in the morning I cooked it only to the boil. After rinsing, I added grated almonds (bademi), cashews (indijski orasi), and goji berries (godži bobice), followed by three eggs, then shaped them into patties, and on medium heat, I fried them for a minute or two on each side.

I had low expectations for the reason I was not privy to the vegetarian cuisine that much, but I admitted I was wrong—the result was amazingly tasty Neanderthal burgers! The nutrition value was off the chart, and combined with mustard and ketchup, it was one great meal of the day. From what I learned in this cooking lesson, the real benefit lies in the zillion combinations with different seeds, pulses, and nuts. I am more than sure that with this, we now have one more regular recipe in the house.

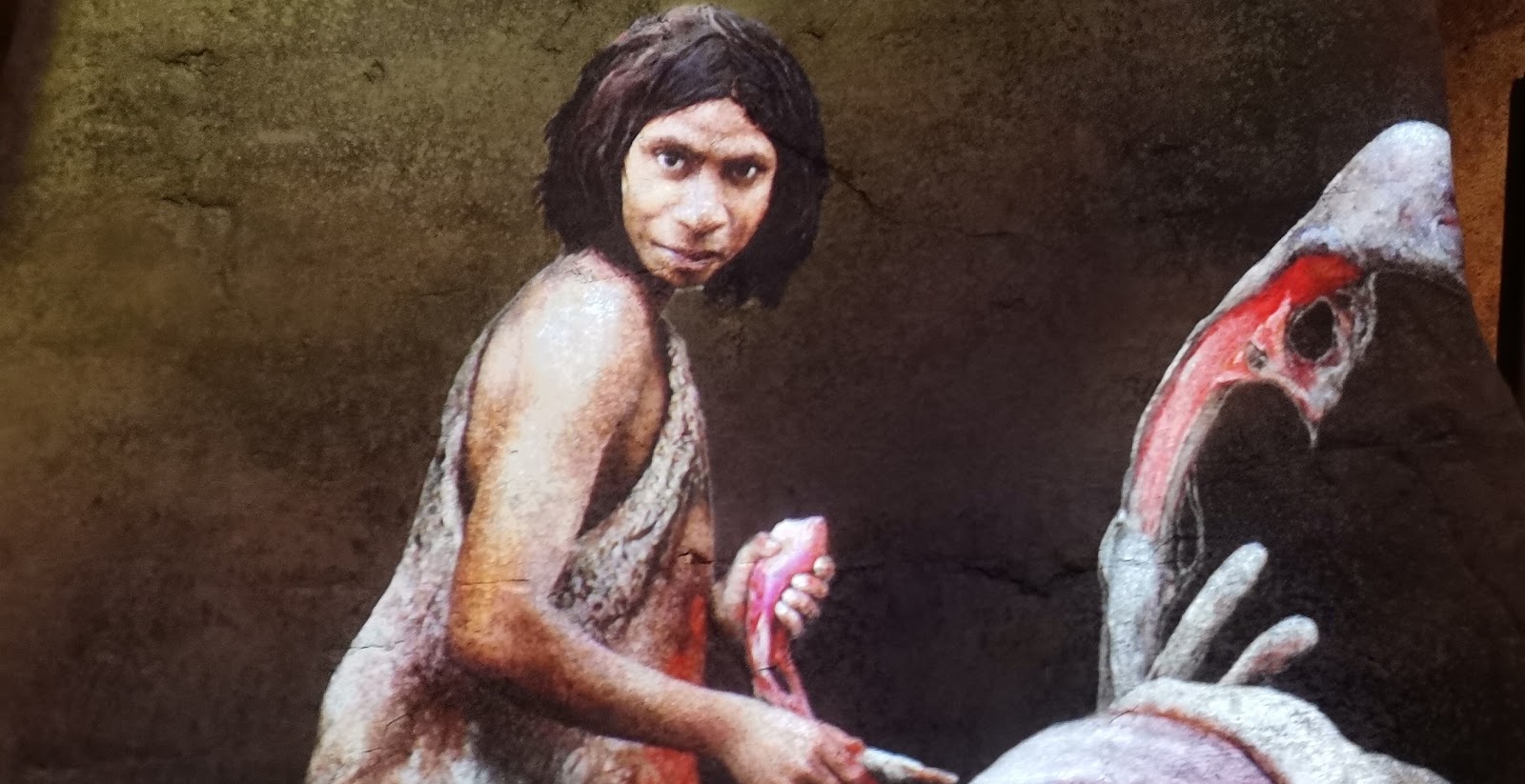

First image by Tom Björklund from the Neanderthal exhibition at the Natural History Museum of Denmark:

https://snm.ku.dk/english/exhibitions/neanderthal/

Refs:

* https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3166335/

https://snm.ku.dk/english/exhibitions/neanderthal/

Refs:

* https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3166335/